Ministry With And Among People in Poverty

The Mission Statement of GodPASTOR MARC MILLER+, DIRECTOR FOR EVANGELICAL MISSION, NW OHIO SYNOD

May 17, 2013

In Luke 4:16-21, Jesus sets forth what some call “the mission statement of God” as he quotes Isaiah, and embraces his own call. As the fulfillment of the promise of the Messiah, Jesus demonstrates that in him, the reign of God is already here. How do we do know? What are the signs that the Messiah has truly come? The first sign we get that the kingdom of God is at hand is that God anoints Jesus to bring the good news to the poor. And if that is at the heart of Jesus’ mission, it is at the heart of our mission as well.

What if the church embraced “the mission statement of God” (Luke 4:16-21) as its own mission statement? What would our mission—and our congregations—begin to look like if it did?

In our American middle-class way of thinking, we often do not share Jesus’ missional vision. We blame the poor, we mock them, and we sometimes even demonize them for sapping the strength of the nation. Blaming people for being poor has no place in the mission of God. Regarding the poor, Jesus says, “Give to everyone who begs from you,” (Matthew 5:42) and indeed, throughout his ministry, Jesus ministers with and among the poor, and proclaims to them the good news concerning himself (Luke 6:20; Matthew 11:2-6).

Jesus shows great love for the poor by sharing daily bread and the Bread of Life (himself) with the poor. In what ways does our congregation share daily bread and the good news of Jesus Christ with those living in poverty?

There are many scripture stories about God’s provision for the poor. A refrain throughout the Old Testament is that the people of God are to always extend God’s mercy to “the widow, the orphan, and the sojourner”, that is, the poor and the vulnerable. In Jeremiah 7:5-7, Israel is told that if they do not oppress the poor, God will dwell with them. Psalm 34:6 declares that God hears the cry of the poor, and delivers them from their troubles. And God warns Israel that if they abuse the poor, and take advantage of them, God will bring destruction upon Israel

(Amos 8:4-10). Conversely, when the hungry are fed, it is a sign that we have served Jesus himself (Matthew 25:40), and it is a sign of the presence of God’s reign among us, as in Mary’s song of praise (Luke 1:46-55). Some theologians have noted that God demonstrates a “preferential option for the poor”, that is, that God most loves, protects, and advocates for, those who are poor.

These Bible passages highlight God’s love and priority for those who are poor. Why do you suppose that we seldom study scripture passages that speak of God’s love and care for the poor? Does it seem right that God loves the poor more than the rich?

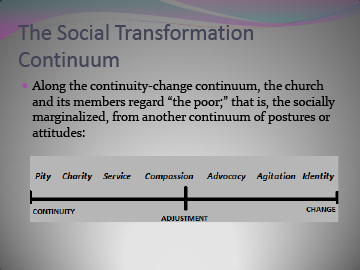

But simply caring for the poor is not enough. Bishop Wayne Miller of the Metropolitan Chicago Synod, ELCA, in his excellent paper, Mission Among People in Poverty: A Christian Theological and Ethical Call to Social Transformation (December 23, 2011), identifies a continuum that describes our connection to the poor. It begins with pity, the emotion that one feels when encountering someone of a lower status, and ends with identity, where Bishop Miller observes, “We no longer bring Christ to the poor, we find Christ in the poor.” Engaging in mission among people in poverty will inevitably, for Jesus’ sake, transform us who see the poor as “them” to recognize them as”us”, our sisters and brothers in Christ.

As you study the movement from “pity” to “identity” in Bishop Miller’s paper, where do you see yourself along that continuum? Where do you see your congregation?

Jesus says, “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself,” (John 12:32), and as he draws us all together in his salvation, he eliminates the barriers between us. There is no longer Jew or Greek, slave or free, legal or illegal, gay or straight, poor or rich, “…for all of you are one in Christ Jesus. “ (Galatians 3:28). When, in our perception, the poor are “us” rather than “them”, we will see and experience Jesus in the poor, and we will want to be one with the poor, in Christ. This is what Paul is referring to when he speaks of our relationships in the light of Jesus’ resurrection: “From now on, therefore, we regard no one from a human point of view..” (2 Corinthians 5:16), but rather, we see Christ in everyone, and we see each other through the lens of Jesus’ saving love.

May the Spirit of Christ help us all to be watchful about how we refer to other people as “them”, especially as it pertains to those living in poverty. Name and celebrate ways in which you and your congregation, with the help of God, have overcome referring to others as “them”, and have learned to see Christ in all people.

There are two factors which are pushing the church towards mission among people in poverty: the crushing need of people in America today, and the decline of the church in our nation. It is also the Holy Spirit, working through these factors, who is opening our hearts and minds to hear and respond to “the mission statement of God”.

The growth in poverty in the U.S. has been well documented in many ways by many sources. Seeing the exploding number of those going to congregational food banks is plain evidence, and Bread for the World does a marvelous job of chronicling the growth in poverty in the U.S. A study just found that poverty grew in Ohio 58% from 1999 to 2011 (Toledo Blade, February 1, 2013). Our perception that there is growing poverty around us is supported by facts.

In what ways have you noticed growing poverty in your community? How has your perception of “the poor” changed in recent years?

Meanwhile, the attendance, finances, and influence of the church, particularly our Evangelical Lutheran Church in America congregations, continue to wane. It is not a coincidence that as our church declines it is increasingly sensitive to the plight of people in poverty! As our church and our congregations are increasingly marginalized by the culture, it is not surprising that we are more aware of those on society’s margins. We are becoming increasingly disoriented because of major changes in our nation and in our world, and we are perhaps more ready to embrace God’s work of doing ministry with and among the poor.

Consider how your congregation’s prestige and influence have grown or decreased over the years. Do you find, as many Lutheran Christians have found, that as our influence in our community has waned, that we are freer to re-examine our mission, and re-orient around “the mission statement of God”?

Praise God, the changes in our church demonstrate that we are paying attention to the work of Jesus! We are embracing “the mission statement of God!” More than half of all congregations in the Northwestern Ohio Synod have either an active food ministry, and/or a meal that is served to the poor in the community. These are great first steps towards identifying with the poor. May God give us the strength and commitment to continue to develop this mission among the poor—our sisters and brothers in Christ. May God also give us the wisdom to go deeper in identifying the connections between hunger, homelessness, mental illness, addiction and violence. May we also be more aware of the “sojourners” among us, those who are living and working among us who have recently come to this country, with or without documentation.

What is your congregation’s ministry for those who are hungry? Has your congregation been affected by growing hunger and poverty in your community? And how is your congregation welcoming the sojourner in your community, and addressing the other factors that cause people to become poverty-stricken?

Our church’s mission will increasingly be linked with the poor. As we continue the process of understanding that the church is not called to achieve numerical success (the world’s standards), but rather to exhibit gratitude to God for Jesus, and to follow Jesus as his disciples, we will turn more directly to scripture to learn and to embrace the true, biblical mission of God, which is to share good news with all, and especially with the poor. As our congregations become more welcoming to those in poverty, and further become “us” with those in poverty, we will grow in generosity and collegiality, two of the hallmarks of the poor. Paul tells us that the relatively poor Philippians were a tremendous example as they gave more generously than all the others, giving out of their “extreme poverty” (2 Corinthians 8:2). Indeed, Gallup studies show that the poor are more generous than the rich. A recent Gallup study showed that those earning less than $10,000 per year give away over 3% of their income, while those earning over $100,000 give away less than 2%. We have studied the giving patterns of congregations in our Northwestern Ohio Synod, and we have seen that those in poorer congregations do indeed give a higher percentage of their income than those in wealthier congregations.

It is a fact: by percentage, the poor are more generous than the rich. Why is that so? What does that mean for the rich? Reflect again on how Jesus warns of the dangers of being rich.

Jesus says, “Blessed are you who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God. Blessed are you who are hungry now, for you will be filled.” (Luke 6:20-21). Mary says that, in the reign of God, the hungry are filled with good things, and the rich are sent away empty (Luke 1:53). Lazarus is raised to paradise as the rich man suffers (Luke 16:19-31). And Jesus prays that God’s will be done on earth as it is in heaven (Matthew 6:9-13), where all will experience the eternal grace and goodness of God. May we, the church of Jesus Christ, give thanks for the grace, salvation, and provision of God through Christ Jesus, and may we know that we are all called together to serve “the mission statement of God” in our communities.

Everything in our lives in Christ flows from the knowledge that God gives us everything we need (Matthew 6:25-33, 7:7-11). How will you and your congregation participate in “the mission statement of God” so that those living in poverty also receive all the gifts that God offers, especially daily bread, and the Bread of Life, the good news of life in Christ?

LINKS AND RESOURCES

2013 NWOS Resolution for Intentional Ministry with People living in Places of Poverty

Bread for the World, www.bread.org

Miller, Wayne, Mission Among People in Poverty: A Christian Theological and Ethical Call to Social Transformation

Sufficient, Sustainable Livelihood for All, ELCA Social Statement, 1999

Mission Among People in Poverty: A Christian Theological and Ethical Call to Social Transformation

Bishop Wayne Miller, Metropolitan Chicago Synod, ELCA

Since my election as Bishop of the Metropolitan Chicago Synod, in 2007, I have served on a committee of ELCA bishops focusing on ministry among people in poverty. Needless to say this is a matter of grave and perennial concern in an urban metropolitan synod like our own. And yet for all the genuine passion and commitment of our church toward the poor and the marginalized in our society, our actual transformational impact on the conditions of privilege, economic disparity and unequal opportunity that perpetuate conditions of poverty and marginalization has been modest, at best.

Now that I have been invited to serve as chairperson or convener of the MAPP Committee, referenced above, I find that I am drawn more deeply into the question of what it might actually mean to be a church effectively engaged in the social transformation process necessary to change the accelerating prevalence of poverty and marginalization in North American Society… and, in doing this, to move from merely ministering to the poor, towards engaging with the poor in Christian mission to the world.

Are We Serious About This?

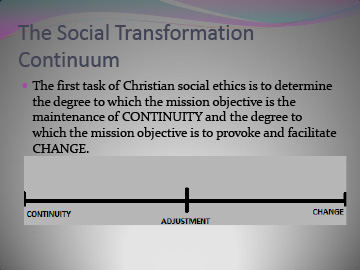

Responding to poverty may or may not be the same thing as eliminating it. It is not at all clear which of these represents our actual mission objective. When making presentations to congregations and groups of pastors on the subject of renewal and transformation, I often begin with this question:

Do you believe that Jesus died to change the world or to keep the world from changing?

My experience has been that most people say that Jesus died to change the world. Most people live as if he died to keep the world from changing. In fact it is a more complicated question than it might seem.

When we consider the changes in creation, for example, brought on by generations of degradation at the hands of human irresponsibility and exploitation of the environment, one might quite appropriately say that Christian social ethics call us to stand boldly for natural continuity and resist the change being brought on by human sinfulness. Similarly, when we see the institutions of “mainline religion” deteriorating in an environment of secularization, self-absorption, cultic pseudo-religions, materialism and consumerism, we might well be motivated to cry out for continuity and a return to our former values of decency, piety, and dedication to building institutions for the common good – institutions that resist these destructive trajectories of change.

But the conditions of poverty, alienation, discrimination, racism, classism, economic and educational disparity, lack of access to health care and social support services – forces that elevate some members of our society while crushing others, bear witness to the demonic side of social continuity. Sometimes the defense of social continuity, our attachment to familiar patterns and structures, has the unintended consequence of enabling and protecting personal sin and collective evil.

To label individual Christians or Christian social ethics, therefore, as either “conservative” or “progressive” is both meaningless and demeaning. The Church and its members are called to a much more careful and thoughtful discernment, on an issue by issue basis, of where we need to stand and how we need to move along a continuum of social transformation:

On the question of poverty and social marginalization, the analysis that leads to action is further complicated by the fact that the “social position” of a particular denomination and its members has an enormous impact on how the mission is interpreted. Those on the high side of power and privilege have an almost insurmountable “self-interest” in preserving continuity. Those on the low side of power and privilege have an equally compelling self-interest in turning an unjust society on its head at any cost.

As a result, we in the ELCA must begin our engagement with mission among people in poverty by asking ourselves some very hard questions about our passion and Intention to transform the basic structures of society that perpetuate and encourage conditions of greater poverty and marginalization for some social groups than for others.

Who Are We?

From a confessional and theological point of view, Lutheran identity is grounded in the belief that:

All that I am and all that I have comes by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone.

This confessional self-understanding is a “great equalizer,” placing everyone on level ground before God and dispelling any pretenses of status or privilege. But as a matter of practical sociology, the story is quite different.

As a denomination, the ELCA is unmistakably and inescapably identified with the high side of power and privilege in North American society. We are 97% white, mostly of Northern European heritage, but long-since “Americanized,” with English being our predominant language.

As a group we are highly educated, middle class, upwardly mobile, patriotic, and law-abiding. It is difficult to determine the exact percentage of present ELCA Lutherans that live at or below the federal poverty level, but based on other social position data, that proportion is likely quite small. Even if you add in every single person of color in our Church, regardless of their socio-economic status, the number of ELCA Lutherans that could rightly consider themselves socially marginalized remains small. If you include, gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered Lutherans in the marginalized group, the percentage goes much higher. But this last group, though socially marginalized, may or may not consider themselves among “the poor” of society.

The obvious implication, for the ELCA as a whole, is that for most of us most of the time, “the poor” are someone else. They are more often object than subject; more often a category than a relationship. For us and for the part of North American society most like us, there is a compelling self-interest in maintaining social continuity rather than provoking social change.

Why Are We Here?

The mission of the Church, the reason we are here, is to call the world into a deeper relationship with God through Jesus Christ by the way of the Cross.

This is the only mission that belongs uniquely to the Church and it is the only mission that no one else will do if we do not do it. All Christian speech and all Christian action either lead toward this relationship as its goal or come from this relationship as its source. Our work is either a means of grace driving toward God or a gift of grace coming from God through us to the world. Our work is the predicate connecting the subject with the object, the source with the goal, the alpha with the omega.

In general, Lutherans do not use mission among people in poverty as a means of grace by which to call others into a deeper relationship with God. We are suspicious of a Christianity that uses ministry among people in poverty as a covert evangelism tactic. We are much more comfortable seeing our work among the poor as a gift of grace given freely and unconditionally on Christ’s behalf.

But do we really intend our work among people in poverty as God’s gift, or do we see it as our gift? Do the poor and the marginalized receive our action as God’s gift or as ours? Within these questions is the distinction between work among the poor as Christian witness or merely as humanitarian social work. And for most, awareness of the religious source and the religious goal of this work grows by walking a life-long path toward deeper intimacy with God.

Walking the Path

The most common, uncritical entry point for our way of looking at the poor is PITY: “There, but for the grace of God, go I…” by which we implicitly mean, “I’m not going THERE.” In fact, there is an even more distant position that we can assume, which is INDIFFERENCE to the poor. But my experience is that complete indifference is rare among those who participate in our faith communities:

Our Church and its members, however, do not only view the poor and the marginalized from a posture of pity. There is in fact a continuum of attitudes and postures that corresponds with the social transformation continuum:

Pity

Pity is an emotional response that can only be experienced by someone in a position of privilege toward someone who is “lower” in a social status spectrum. It is a completely subject-object orientation, not unlike Martin Buber’s category of an “I-IT” relationship. Pity is a small opening of the eyes and the heart; it does not necessarily lead to an opening of the hands. Pity offers no challenge whatsoever to the continuity of the socio-economic status quo.

Charity (or Philanthropy)

As most of us are called “forward” on the continuum from pity, the next experience is charity. Charity translates pity into action, essentially through a voluntary redistribution of material benefits. If you are hungry, charity calls me to give you half of my sandwich… or perhaps a grocery discount card. If you are poorly clothed, I may give you an old coat that I was planning to throw away. If you are holding a tin cup, I may place a 5-dollar bill in it.

When the conditions of poverty are too great for us to make a meaningful response on a private basis, we may build philanthropic organizations which have the capacity, through pooled resources, to meet more material needs for more people and thereby provide more relief for the crushing impact of socio-economic disparity. In addition, philanthropic organizations have the secondary gain of building strong purposeful community among the privileged who gather regularly for fund-raising activities and who usually comprise the boards of directors for these philanthropic organizations.

Charity and philanthropy are both admirable and necessary. But for all their goodness, they do virtually nothing to disrupt the continuity of the social structures that produce poverty and marginalization. They provide HELP rather than HOPE, and they may or may not lead to interpersonal relationships between the poor and the privileged. The chasm remains.

Service

Service moves charity from an economic transaction to personal involvement. The stewardship focus here is on time and energy rather than treasure. Individuals or groups may build homes for the poor or sandbag overflowing rivers or distribute meals at a soup kitchen instead of just paying for the groceries.

In middle and upper class North American culture, the movement from charity to service is not insignificant. For most people in this part of the privilege structure, TIME may actually have more value than MONEY. Because of this, service almost always involves personal sacrifice; the giving up of something precious for the sake of someone else. Charity, on the other hand, may not require sacrifice at all, but only the spilling over of surplus abundance, the “crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table.”

Service, by its very nature, also calls the privileged toward an actual relationship with those being served. And this relational dimension may actually be a useful distinction between charity and true service. So, for example, in programs like the popular Feed My Starving Children response to poverty, both resources and time are being shared. But the relationship building occurs on only one side of the divide rather than across the divide. This difference may categorize efforts like this more as charitable-philanthropic responses than as ministries of service.

In either case, service seems to call for a deeper personal involvement with the poor but still leaves us in a position of maintaining social continuity rather than effecting systemic social transformation.

Compassion

For at least some of those engaged in Christian service to the poor, a remarkable event occurs. It is an opening of the heart in compassion; that is, the experience of suffering with the one who is suffering. Compassion represents the capacity to feel those things in ourselves that we hold in common with those who live on the other side of the divide.

The movement into compassion is affective and invisible. It may not lead immediately into a change in what we do or how we live, but it will change immediately how we do it and why we do it and how we feel about it while we are doing it.

Compassion is the fulcrum point of the continuum because it opens the door for us to move from “I-IT” to “I-THEY” to “I-THOU” in our relationship with those on the other side of the socio-economic chasm, and, in so doing, it drives us from the bias for social continuity toward a bias for social change.

Advocacy

Compassion permits those of us with privilege the audacity to speak in the public square for those who have no voice in the public square. It not only allows, but categorically requires us to build deeper and more honest relationships with those on the other side of the divide, so that we know we are advocating for the poor and not merely pushing an alternative personal political agenda.

Doing the work of advocacy without attending to relationships with the poor can easily detach advocacy from its explicitly Christian motivation. It can drift into an expression of middle class shame rather than an expression of gratitude for Christ’s boundless power of redemption, and in that drift, weaken its own moral and ethical authority.

Advocacy does not eliminate the chasm between rich and poor. When the Church speaks in the public square we are given that voice by virtue of our privileged position in society, and without that privilege no one in power would listen to us any more than they listen to the poor themselves.

Nonetheless, advocacy is an important advance on the continuum in that it moves our response to the poor from the private realm to the public realm and from a purely personal to a necessarily systemic response to the conditions that perpetuate the suffering of the poor and the marginalized.

Agitation

Agitation moves us into direct confrontation with the systems of disparity between rich and poor. It compels the privilege structure to look and to respond. Agitation is Nathan saying to David, “You are the man!” and then demanding repentance and amendment of life.

Agitation is an organizational recognition and response to the injustice that entire categories of human beings are being prevented from being who God is calling them to be and prevented from doing what God is calling them to do, simply by virtue of the category that society has assigned to them.

Agitation requires building the power of organized people and organized wealth toward a common objective to constrain sin and then change the social system, because, “No one can enter a strong man’s house to liberate what he possesses without first binding the strong man.”

Agitation is the point on the continuum at which the ELCA, and denominations like it, begin to divide and differentiate, because it is very difficult to reach this point without valuing socio-economic change at the expense of socio-economic continuity. And only a few of us are ready for this.

Identification

Identification is the rare and wonderful miracle in which the chasm between rich and poor, privileged and invisible, disappears. Los Otros son Nosotros. I and THOU are simply US. Identifcation is the embodiment of Kenosis. Identification is the vision proclaimed inPhilippians 2 when Christ did not consider equality with God a thing to be grasped, but instead emptied himself. And then again, inMatthew 25, Jesus equates identification with the poor and identification with him. We no longer bring Christ to the poor, we find Christ in the poor. And it is through deepening our relationship with the poor that we, who have been clinging to our privilege, grow more deeply into our relationship with God.

It remains an open question whether this identification actually exists in real time and space, or if it is only a consummation devoutly to be wished. But if it comes; when it comes, the old heaven and the old earth pass away. Everything changes. There is no continuity between the old creation and the new.

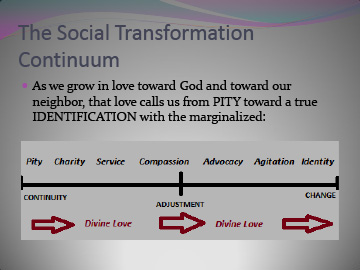

Navigating the Continuum

From a Lutheran theological perspective, movement along the social transformation continuum is not, strictly speaking, a function of choice or free will. We do not move along the continuum, we are moved along the continuum by the power, the force, the energy of divine love working on us, within us, and through us:

The choice involved for us, on a day-by-day basis, is whether or not we can take the risk to surrender ourselves to this divine love and trust it to lead us where we need to go even if it is not where we exactly want to go.

The entire challenge of a life of Christian discipleship is learning to live with our hands open: opening first to receive the abundance of God’s grace – opening again to release the abundance of God’s grace into the world.

The hidden cost of living with open hands is that one must release what is there FIRST so that God is free to fill our hands again with the new abundance that is waiting. Between the surrender of what we have and the receipt of what God is sending, there is only emptiness.

So how does a Church like the ELCA, given who we are socio-economically, respond to the very difficult challenge offered by this social transformation continuum?

Responding in Faith and Hope

No matter how much we may want to, the ELCA, as a denomination, is not going to walk the length of the continuum. Our entire structure: our constitutions, our demographic composition, our constituency, our sophisticated academic leadership preparation process, our authority and administration patterns, our vestments, our generally accepted accounting principles, our social ministry organizations, the arrangement of our office building, all conspire to keep us too locked into continuity with the systems of power and privilege to be free to identify, as an institution, with the poor and the marginalized. Analyzing and blaming ourselves for our status and our behaviors of privilege will not fundamentally change this.

On the other hand, within our denomination and our global communion there are places where this identification can occur. Lutheran communions in the “global south” can do it, because they are churches rising up among people in poverty. Congregations, domestically, that serve among the marginalized can do it for exactly the same reason. And it is certainly still true that individuals living within our congregational communities, even in places of wealth and privilege, may experience the love of God pull them toward compassion and eventually identification with the poor.

But the role of synodical and churchwide expressions of our denomination is different. Ours is the power to inspire, facilitate, and extend the reach of those among us who are walking the path.

We can INSPIRE those in the journey by persistently and joyfully calling our congregations and our members into pinpoint focus on the mission of the Church to call the world into a deeper relationship with God, through Jesus Christ, by the way of the cross. Then, we trust that this growing relationship with God and ONLY this relationship has the power to fill people with the divine love that drives them forward on the path.

We can FACILITATE those on the journey, primarily by calling, preparing, and releasing congregational leaders formed by our central identity, mission, and vocation – leaders who will challenge, encourage and support congregations who are forming disciples around that deepening relationship with God and surrendering the attachments that separate them from the poor and marginalized.

We can EXTEND THE REACH of those on the journey by connecting them with others who are also walking the continuum and by creating organizational and institutional structures that allow individuals or congregations to keep moving as they are called, by love, to do so.

Mission Among People in Poverty continues to be one of the greatest challenges and the greatest opportunities facing our Church. And for those of us in structural leadership within the ELCA, this may be a critical time for us to step back and refresh our vision of where we are, where we are going, and who is accompanying us on the journey.

Implications and Critical Questions

Within the synods of the ELCA, what are the current manifestations of each of the “steps” along the path from PITY to IDENTIFICATION? Where are we strongest and where are we weakest along that path?

The ELCA and the LWF are noteworthy for their network of social ministry organizations. Where do we place these organizations along the path? Do they have effect of calling people forward on the path or keeping them where they are?

The ELCA has put tremendous effort into creating congregations in communities of color and communities among the poor, but sustaining these communities over time is a persistent problem for us.

- What are the factors that make the sustenance and growth of these communities so difficult?

- Would it be worth the time and effort for the MAPP Committee to assume the challenge of creating new and more effective models for congregational mission among the poor?

- What do we see as the role or responsibility of synods and churchwide structures in sustaining mission among the poor?

As congregations or individuals working among the poor reach the “agitation” stage of engagement, do synods or churchwide structures have any appropriate top-down role to play in this stage, or is agitation, by definition, an expression of the poor, and those who identify with them, “reaching up” to claim their God-given power, freedom, and vocation?

If “race and racism” are demonic forces that structurally prevent our congregations from moving forward on the path, can we or should we re-frame the conversation about race in terms of its destructive effect on congregational mission and personal spiritual growth? How would this change the nature of our engagement with anti-racism?

How explicitly does our ministry among people in poverty need to remain “Christian?” Do good works alone bear witness to the love and power of Jesus or must we continue to articulate Jesus Christ as the source and the goal of this work?